I’m thrilled to host an author Q&A today with Janet Wertman on her book Nothing Proved – the first in her Regina series which charts Elizabeth I’s journey from bastard to icon.

A huge thank you to Janet for answering my questions and to Cathie of The Coffee Pot Book Club for coordinating this exciting opportunity!

Danger lined her path, but destiny led her to glory...

Elizabeth Tudor learnt resilience young. Declared illegitimate after the execution of her mother Anne Boleyn, she bore her precarious position with unshakeable grace. But upon the death of her father, King Henry VIII, the vulnerable fourteen-year-old must learn to navigate a world of shifting loyalties, power plays, and betrayal.

After narrowly escaping entanglement in Thomas Seymour’s treason, Elizabeth rebuilds her reputation as the perfect Protestant princess–which puts her in mortal danger when her half-sister Mary becomes Queen and imposes Catholicism on a reluctant land. Elizabeth escapes execution, clawing her way from a Tower cell to exoneration. But even a semblance of favor comes with attempts to exclude her from the throne or steal her rights to it through a forced marriage.

Elizabeth must outwit her enemies time and again to prove herself worthy of power. The making of one of history’s most iconic monarchs is a gripping tale of survival, fortune, and triumph

Q&A

1. Tell us about your choice of title, “Nothing Proved” and why you chose it. Does Elizabeth have something to prove?

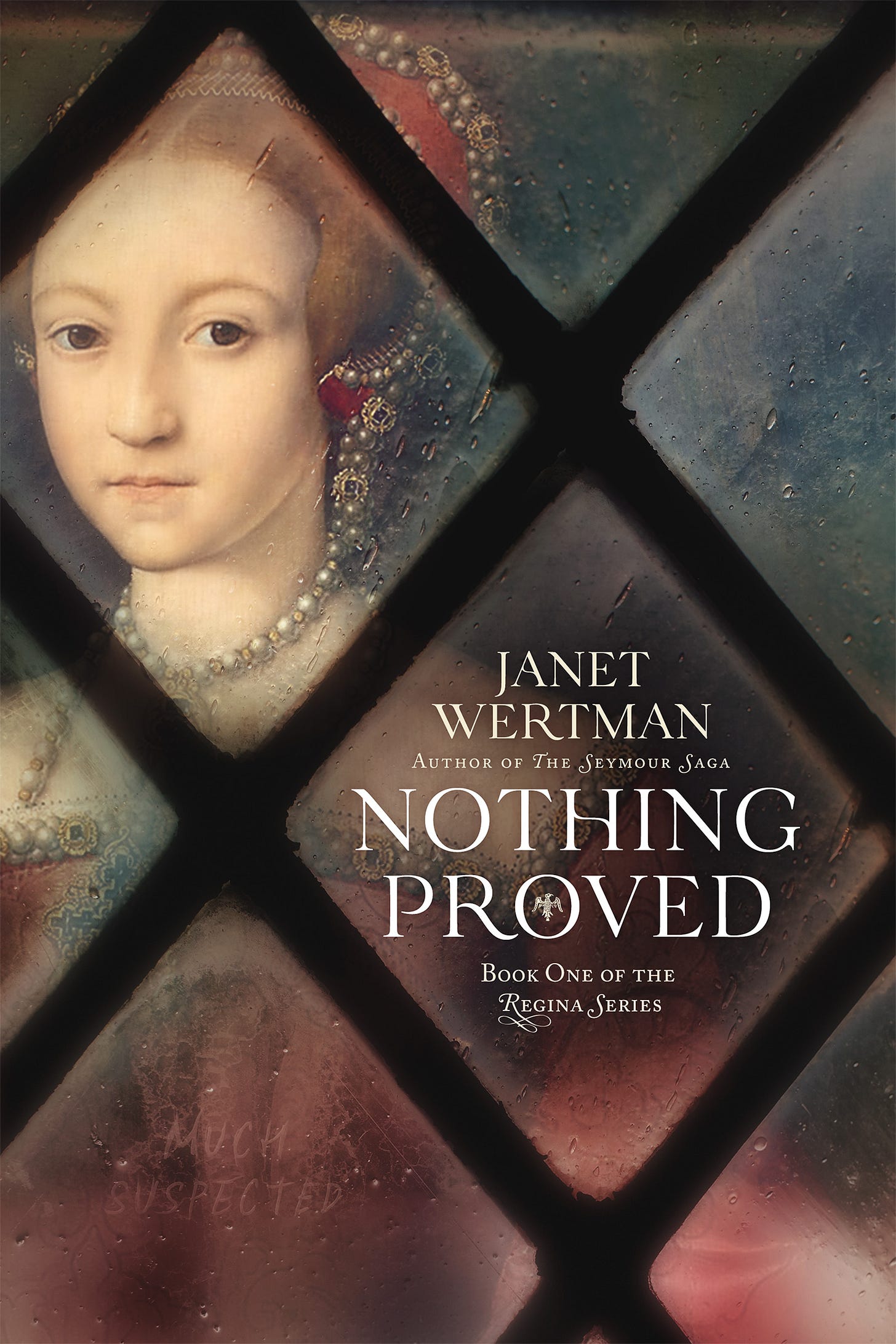

Elizabeth absolutely had something to prove, but that’s not where the title came from. Rather, it was the dramatic closing line to a poem she wrote while she was imprisoned at Woodstock. The full poem is wonderful, but accusatory enough of her jailers (“God send to my foes all they have taught”) that they took away her paper and pens. In a fit of pique, she used a diamond ring to carve the last two lines in a window pane: Much suspected by me, Nothing proved can be. To me, those lines described the circumstances surrounding so many of the challenges she endured during this period of her life and made the perfect book title. Well, “Nothing Proved” was the perfect book title– and the cover shows a faint “Much Suspected” on the bottom left side.

2. What drew you to focus on Elizabeth Tudor's early life before she took the throne? What moments did you feel were integral to this part of her story?

The story begins when she is fourteen, but I included a Prologue from the time when she was eleven, the earliest justifiable time I could put Elizabeth, Robert Dudley, and William Cecil in the same room. I wanted to show the origin of the relationships that would last – and remain remarkably consistent – all Elizabeth’s life.

3. Elizabeth demonstrates vulnerability when faced with imprisonment and death but also great determination and intelligence. How did you find writing her as a character?

I loved it. Writers of historical fiction are often criticized for giving their women anachronistic autonomy and attitudes - but Elizabth truly had those characteristics, and used them, so I knew I had a free pass.

4. You choose to focus some of the narrative on William Cecil and explore how his fate is tied to Elizabeth’s. Why did you choose his story specifically alongside Elizabeth’s?

William Cecil was one of the most important people in Elizabeth’s life – and after he died, his son took his place. Giving him a voice now allowed me to establish his loyalty and earnestness. It also allowed me to include certain events that Elizabeth would not have known about, as well as provide independent corroboration of her judgment. He will not have a voice in future novels (though his son will provide the epilogue to book three).

5. Were there any characters you found difficult/challenging to portray and write about? Why?

Mary was such a sad character at this time in her life that despite her terrible errors in judgment I felt bad piling on. At the same time, I had to: Mary’s mistakes taught Elizabeth so many key lessons and I needed to give them their full expression. Not necessarily for this book, but for books two and three when Elizabeth is on the throne and faced with many similar choices.

6. Elizabeth’s story has poignant parallels to that of her mother, Anne Boleyn, such as her time in the tower and the significance of the date of Elizabeth’s release. Was this something you wanted to draw particular attention to, and if so, why?

I absolutely drew attention to the date – as I tried to dramatize all the events that would have been highly emotional to Elizabeth. The coincidence would have turned despair into confidence, given Elizabeth a sense that a higher destiny approached.

Viewed on its own, Anne Boleyn’s story is a tragedy – but Elizabeth’s triumph vindicates all the wrongs done, transforming Anne’s death into the sacrifice that made it all possible. Jane Seymour was called a phoenix, but I would argue that the true phoenix was Anne, burning so that her daughter could rise (I suspect Elizabeth believed that as well, as she adopted the phoenix as her badge after becoming Queen).

7. The Tudor court was a hotbed of politics, treachery and shifting power. You use the phrase “career courtiers” to describe some of the court nobles such as Winchester and Sussex. Can you give us a bit of context about these nobles and why you used this term to describe them?

From Henry to Edward to Mary, England saw huge shifts in religion – all at a time when disagreement meant death. This opened opportunities for new men to rise – but there were still courtiers like Winchester and Sussex who were able to make believable corresponding shifts in their publicly-expressed viewpoints. This allowed them not only to survive but to maintain power (and helped with continuing institutional wisdom…).

8. You spent fifteen years as a corporate lawyer in New York - has that influenced how you’ve approached the political elements of Elizabeth’s story?

My time as a lawyer taught me there were at least two arguable sides to every story – and thus the importance of nuance when presenting the conflicting facts. It also taught me the importance of building a chain of logic in every argument. Together, these lessons have helped me in all aspects of life, and definitely in trying to explain the ins and outs of Tudor court politics!

9. There are moments of dialogue and letters that seem to be written in Early Modern English such as Elizabeth’s beseeching letter to Mary proving her innocence. What sources did you draw on to write these parts and the novel in general?

“And therefore I humbly beseech your Majesty to let me answer before you, and not suffer me to trust to your Councillors. Yea, I pray you allow me that before I go to the Tower—but if that not be possible, then at least before I am further condemned. Let conscience move your Highness to take some better way than to let be condemned in men’s sight afore my desert is known.”

You caught me. I tend to try to include people’s actual words when they really move me. I always get called out on that in critique groups, so I often end up modernizing things just a touch (though as you can see I still drag my feet, especially when the “classics” are involved!). I will consult letters, ambassadors’ reports, even things like Cobbett’s State Trials to find their actual voices. It’s a visceral thing for me.

10. How did you find blending history into a plot and fictional narrative while keeping historical authenticity?

I have always believed that truth makes the best stories, and that certainly is true of the Tudor era. The history is the history, and part of the way I honor it is to try to align my fictional narrative as closely as possible to the truth. I see my job as connecting the dots between the things we know. In other words, if x happened one day and y three days later, the narrative must explain what was going through people’s minds to allow both those things to be true. That’s actually my favorite part of the endeavor!

Thank you so much for hosting Janet Wertman today, with such a brilliant interview about her new novel, Nothing Proved.

Take care,

Cathie xx

The Coffee Pot Book Club